Pfizer’s EUA Granted Based on Fewer Than 0.4% of Clinical Trial Participants. FDA Ignored Disqualifying Protocol Deviations to Grant EUA.

Out of almost 44,000 trial participants, Pfizer used data from only 170 participants to obtain EUA.

So much has been written about the pivotal Pfizer Trial for COVID-19 (C4591001), that it is sometimes hard to remember that the ‘primary evaluable efficacy’ analysis [Follman DA, 2007) Follmann, D.A. (2007). Primary Efficacy Endpoint. Wiley Encyclopedia of Clinical Trials. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780471462422.eoct341], was granted on the results of 170 subjects out of a trial that enrolled nearly 44,000 people.

What is a Clinical Trial?

A clinical trial is a method used to test a hypothesis and, in context, to determine whether an intervention is safe and effective. As a result, clinical trials are usually heavily monitored, and the protocol (i.e., instructions) for a trial must be followed to the letter so its trial participants (a.k.a., “subjects” or “patients”) can rely on its conclusions. Protocol deviations – not following the instructions – lead to subjects being excluded from a trial and not included for analysis. Generally, any major modifications of the primary endpoint definitions or their analyses will also be reflected in a protocol amendment.

Once a primary endpoint is selected, statistical methods of analysis to test the primary hypothesis can be determined and sample size calculations can be performed to ensure the trial is properly powered. Because of the key role of the primary endpoint in the design and analysis of a trial, it is critical that it be chosen carefully. A primary efficacy endpoint must be precisely specified in advance and should (1) address the primary objective, (2) be ascertainable in all patients, (3) be “fair” to each study arm, (4) have demonstrated or accepted relevance for the population and intervention(s) of the trial, and (5) be sensitive to meaningful changes in a patient’s health. The Statistical Analyses Plan (SAP) would also have been developed and finalized before the database ‘lock’ for any of the planned analyses. It would describe the participant populations to be included and the procedures for accounting for missing, unused, and spurious data.

This was a trial of a brand-new drug and platform of delivery. As such, the first phase of the trial was essentially an exercise to identify the preferred vaccine candidate, dose level, number of doses, and schedule of administration (appropriate dosing interval). The original protocol, dated 15 April 2020, outlined this, and it remained the same until the fourth protocol amendment dated 30 June 2020.

How was the original Pfizer Clinical Trial designed?

The study design described in the protocol released on 15 April 2020 [A PHASE 1/2/3, PLACEBO-CONTROLLED, RANDOMIZED, OBSERVER-BLIND, DOSE-FINDING STUDY TO EVALUATE THE SAFETY, TOLERABILITY, IMMUNOGENICITY, AND EFFICACY OF SARS-COV-2 RNA VACCINE CANDIDATES AGAINST COVID-19 IN HEALTHY INDIVIDUALS. (901AD)32, https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-interim-mth6-protocol.pdf] described a Phase 1/2, randomized, placebo-controlled, observer-blind, dose-finding, and vaccine candidate–selection study in healthy adults. The study, at that point, would evaluate the safety, tolerability, immunogenicity, and potential efficacy of up to four different SARS-CoV-2 RNA vaccine candidates against COVID-19:

As a two-dose (separated by 21 or 60 days) or single-dose schedule

At up to three different dose levels

In three age groups

18 to 55 years of age

65 to 85 years of age

18 to 85 years of age [stratified as ≤55 or >55 years of age]

This trial had many endpoints in terms of safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity. However, the Food and Drug Administration granted Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) on the endpoint of efficacy, evaluating BNT162 vaccines against contracting COVID-19.

The evaluable population was defined as all eligible, randomized participants who received vaccination as randomized within the predefined window, had the efficacy measurement after the last dose of study intervention, and had no other major protocol deviations as determined by the clinician. The efficacy measurement was getting COVID-19 illness and would be assessed by doing a mid-turbinate (nasal) swab in a symptomatic patient.

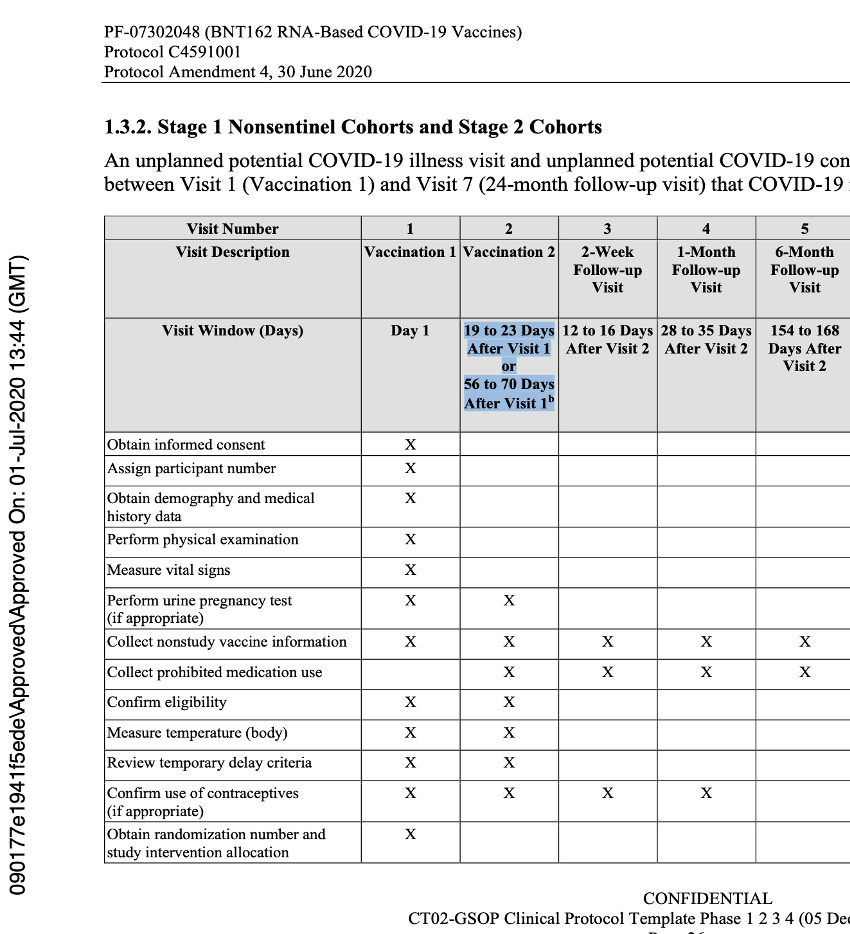

The language of the original protocol describing the second dose of the vaccine stated implicitly that Dose 2 could be either 19 to 23 days or 56 to 70 days after Visit 1, and that the window for Visit 2 was dependent on the dosing schedule that would be selected for Stage 3. This was at the same time they were deciding between either single dosing or a two-dose regimen which could be 21 or 60 days apart (with a range of approved variance) for both regimens.

The issues highlighted continued until protocol Amendment 4, dated 30 June 2020.

Below is an example of the expected flow of that protocol.

[https://phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-interim-mth6-protocol.pdf, p. 1703.]

What happened to the dose and interval between doses by the start of the Phase 3 study?

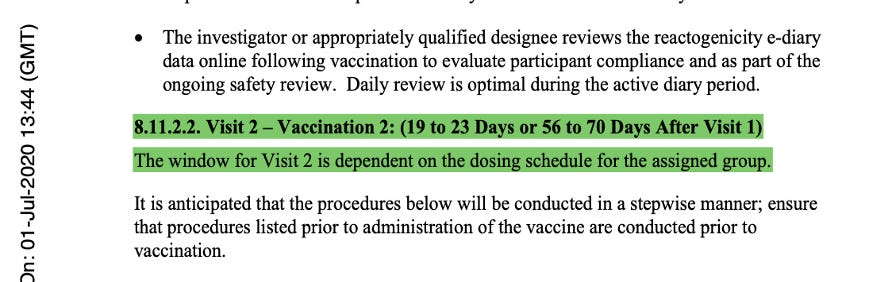

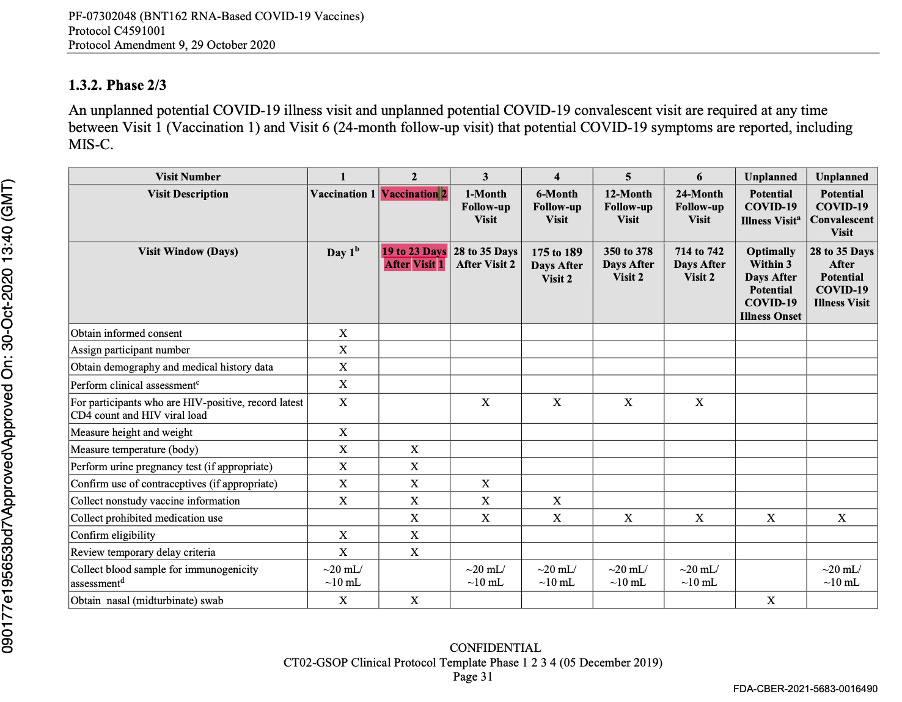

Protocol Amendment 5 was extremely important as it was the last protocol amendment made prior to the commencement of the Phase 3 Trial on 27 July 2020. Dated 24 July 2020, it clearly stated that following regulatory feedback, a single vaccine candidate administered as two doses 21 days apart, would be studied in Phase 2/3 and that the vaccine candidate would be BNT162b2 at a dose of 30 μg. The protocol was changed to reflect this as evidenced below.

[https://phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-interim-mth6-protocol.pdf, p. 1564.]

The description of Visit 2 for the trial participants changed, confirming the dosing schedule had been set at 30 μg with a 21-day dosing interval. The 60-day dosing interval had been discarded. Pfizer settled on the dosing interval window prior to the trial starting, thus seeming to have settled on a predefined window.

[https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-interim-mth6-protocol.pdf, p. 1623.]

How would vaccine effectiveness be assessed?

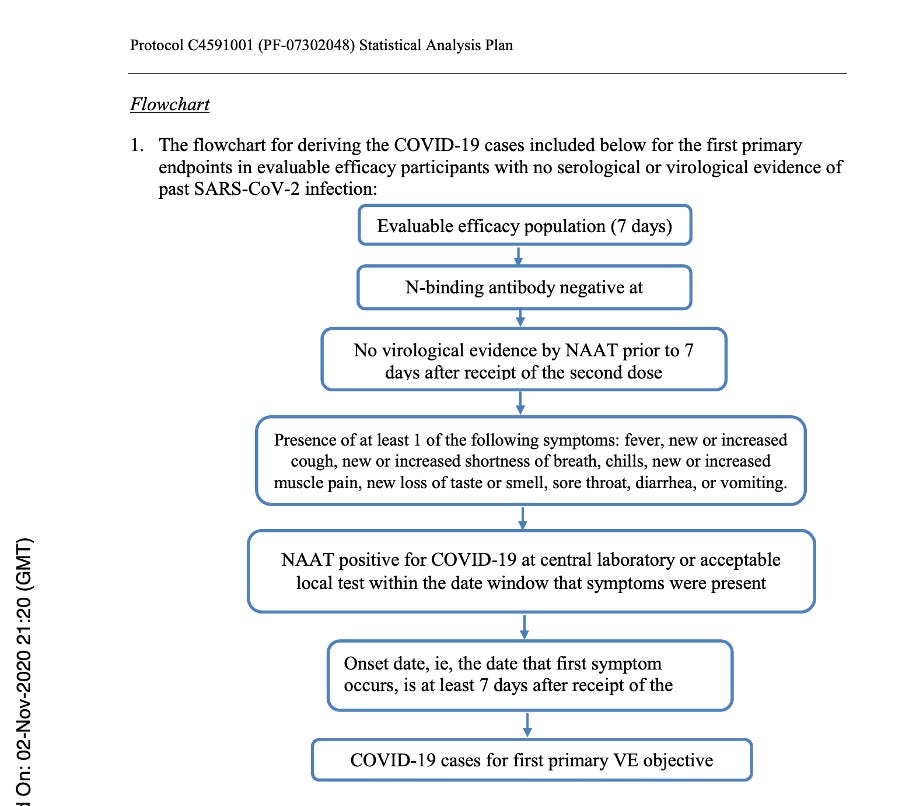

If one wants to determine the effectiveness of a treatment, he or she has to follow the subjects throughout their involvement in the study through surveillance for potential COVID infection. If a participant developed acute respiratory illness, for the purposes of the study he or she would be considered to potentially have COVID illness. Participants were advised to contact the site for an in-person or tele-health visit if such symptoms presented. Nasal (mid-turbinate) swabs would be taken as part of this assessment. The diagnosis would be made based on a positive swab and the presence of at least one symptom from a symptoms list found in the protocol.

Below is a flowchart obtained from the Statistical Analysis Plan [Protocol C4591001 A PHASE 1/2/3, PLACEBO-CONTROLLED, RANDOMIZED, OBSERVER-BLIND, DOSE-FINDING STUDY TO EVALUATE THE SAFETY, TOLERABILITY, IMMUNOGENICITY, AND EFFICACY OF SARS-COV-2 RNA VACCINE CANDIDATES AGAINST COVID-19 IN HEALTHY INDIVIDUALS Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) (GMT). (n.d.), https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-fa-interim-sap.pdf] which clearly outlines those subjects who would qualify for the Primary Efficacy Analysis and, thus, qualify to be part of the evaluable population and be part of the 170 patients on which the EUA was granted.

Flowchart from Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) – p. 58.

How did they decide which subjects qualified for evaluation of effectiveness?

The 170 subjects had to be proven to be without evidence of infection up to seven days after Dose 2. If they became symptomatic later, they would either have an in-person or tele-health visit and get a nasal swab test done. If the swab tested positive and the subject had at least one symptom of COVID, he or she received a COVID-19 diagnosis. The incidence rate per 1,000 person-years would be calculated.

Phase 2/3 was anticipated to be ‘event-driven’, with the assumption of a true Vaccine Effectiveness (VE) rate of ≥60%, after the last dose of investigational product. Therefore, a target of 164 primary-endpoint cases of confirmed COVID-19 due to SARS-CoV-2 occurring at least seven days following the last dose of the primary series of the candidate vaccine would have been sufficient to provide 90% power to conclude true VE >30% with high probability. An unblinded statistical team planned to perform interim analysis for efficacy and futility after accrual of at least 32, 62, 92, 120 and with final analysis planned with accrual of 164 cases.

[https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-interim-mth6-protocol.pdf, p. 1643.]

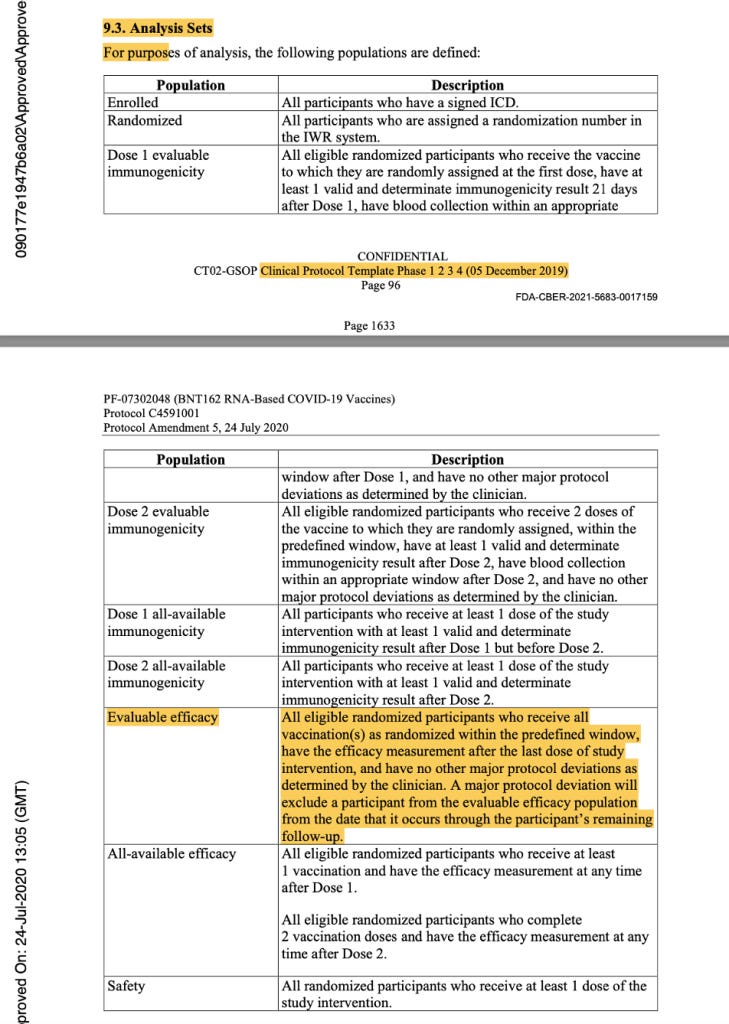

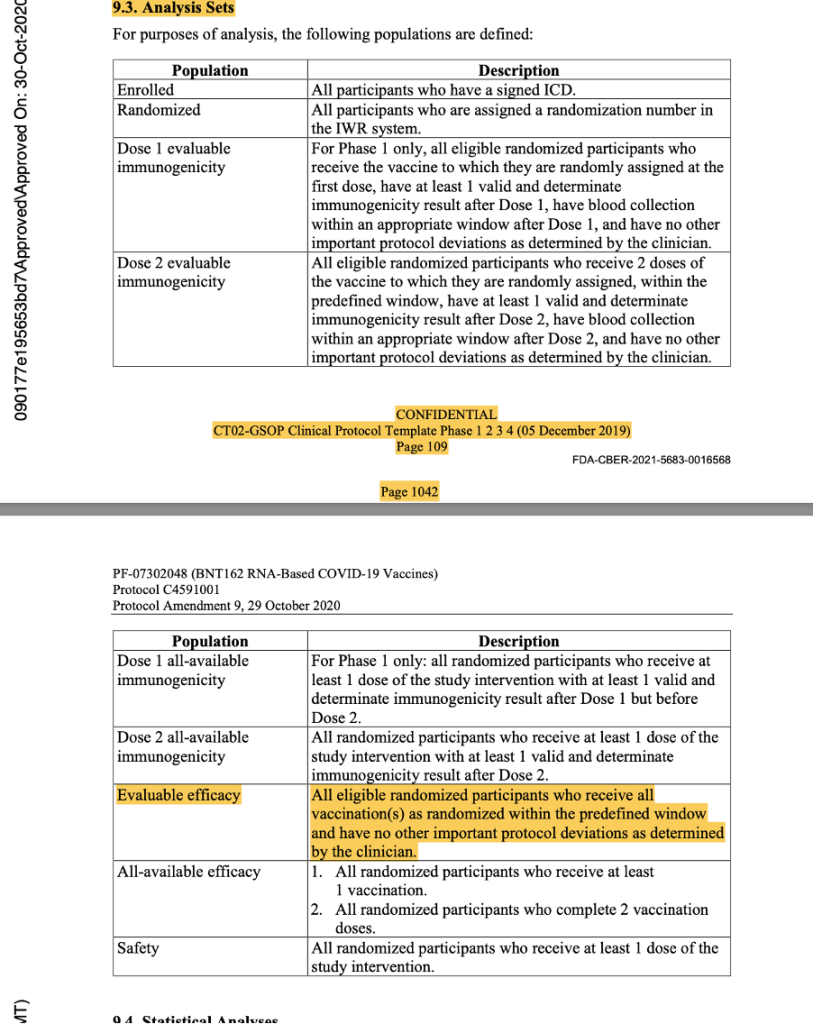

In the analysis sets in Protocol Amendment 5, the evaluable efficacy population was defined as seen in the figure below. Thereafter, it was implicitly printed throughout the protocol that the dosing interval chosen was 21 days between Dose 1 and Dose 2, with a window of allowance of 19 to 23 days after Dose 1. In the statistical analysis sets throughout the protocol documentation, a number was never assigned to the “predefined window.” However, it should have read “as randomized within the predefined window (within 19 to 23 days after Dose 1),” as there was evidence that a window had been defined.

[https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-interim-mth6-protocol.pdf, pp. 1633-1634.]

This was the last protocol change prior to the official start of Phase 3 of the trial. Subsequent protocol amendments dated 8 September 2020, 6 October 2020, 15 October 2020, and 29 October 2020 maintained the parameters outlined above as evidenced by the snapshots below from the protocol amendment dated 29 October 2020.

[https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-interim-mth6-protocol.pdf, p. 1029.]

[https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-interim-mth6-protocol.pdf, pp. 1042-1043.]

The data cut-off date was 14 November 2020, and another protocol amendment occurred on 1 December 2020 prior to issuance of the EUA. It did not outline any changes to the parameters.

Why give this long explanation into the many iterations of the protocol and have so much discussion about the ‘predefined window’?

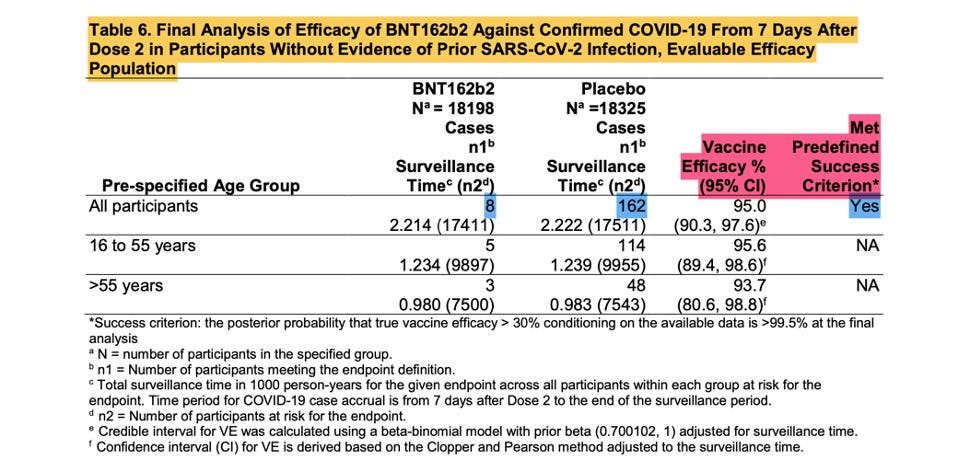

The FDA issued the EUA approving the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine on 11 December 2020.

[Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for an Unapproved Product Review Memorandum Identifying Information. https://www.fda.gov/media/144416/download, p. 18.]

The screenshot shown above is from the EUA Review Memorandum [Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for an Unapproved Product Review Memorandum Identifying Information. (n.d.). https://www.fda.gov/media/144416/download], the Final Analysis of Efficacy against Confirmed COVID -19, that was the basis of the EUA.

These eight positive vaccinated and 162 positive placebo subjects are the ‘170 that changed the world’. Were they as kosher as they were meant to be? Remember, patients that are part of the evaluable population needed to have zero protocol deviations.

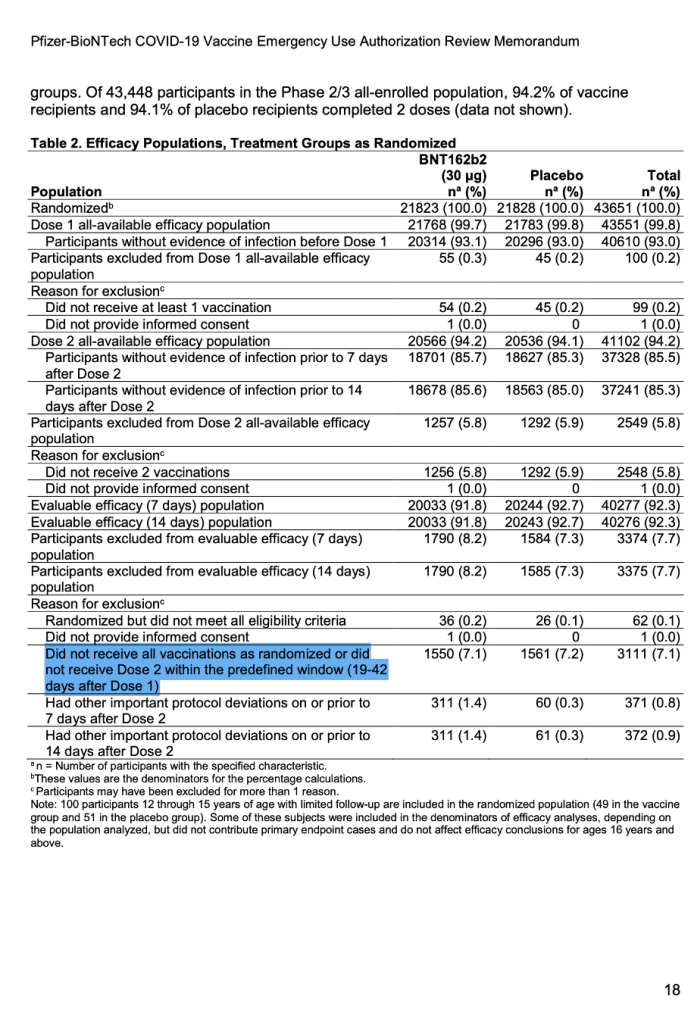

For the first time publicly, a number appeared after the words “predefined window.” (See screenshot below.) It explicitly stated exclusions in the trial would include those who did not receive all vaccinations as randomized or did not receive Dose 2 within the predefined window (19 to 42 days after Dose 1).

[Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for an Unapproved Product Review Memorandum Identifying Information, https://www.fda.gov/media/144416/download, p. 18.]

As a result, the following questions are imperative:

Why, in the first trial of a new drug, would a doubling of the dosing interval that was so painstakingly set earlier be accepted?

Is this a protocol violation?

The protocol described a 19- to 23-day variance of the 21-day dose, as was stated across multiple iterations of the protocol.

Should someone who got vaccinated on day 18 instead of day 19 be accepted?

Why should someone vaccinated on day 41, a bigger deviation of days, be accepted?

How does this bigger dosing variation in dosing schedules affect the efficacy of the drug?

The data simply are not available. Therefore, subsequent studies looking at different dosing intervals individually would be needed. Such a practice would normally constitute a protocol violation, including patients removed from the evaluable population, unless a formal protocol amendment had been filed. The time to file this amendment would also be prior to starting the trial. However, based on the released and publicly available documents, no such protocol amendment exists.

These 170 patients were not easy to find, so how did the authors go about finding them?

On March 1, 2022, a 671-page Pfizer document (25742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-fa-interim-lab-measurements.pdf, https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-fa-interim-lab-measurements.pdf) was released by the FDA. Starting on page 586, we began to find our elusive subjects who would have qualified for the interim analysis. A separate document released publicly on the same date (125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-fa-interim-lab-measurements-sensitive.pdf, https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-fa-interim-lab-measurements-sensitive.pdf) listed the subjects, starting on page 66, who would also qualify to be part of the evaluable efficacy population. Reconciling the two, we were able to find the subjects who became part of the Final Analysis of Efficacy. [https://pdata0916.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/pdocs/070122/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-fa-interim-narrative-sensitive.pdf, pp. 1059-2506.]

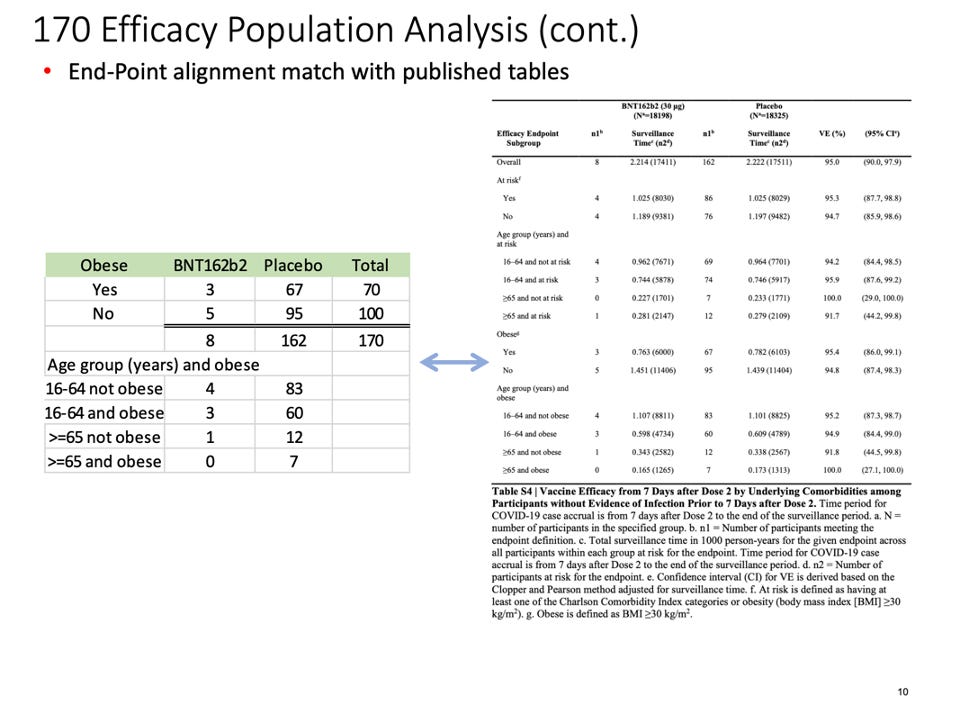

Taking another approach, we also cross-checked the list we compiled against published demographic data available in a New England Journal of Medicine article published on 10 Dec 2020. [Polack, F.P., Thomas, S.J., Kitchin, N., et.al. (2020). Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(27). doi:10.1056/nejmoa2034577, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2034577.]

This table demonstrates our findings:

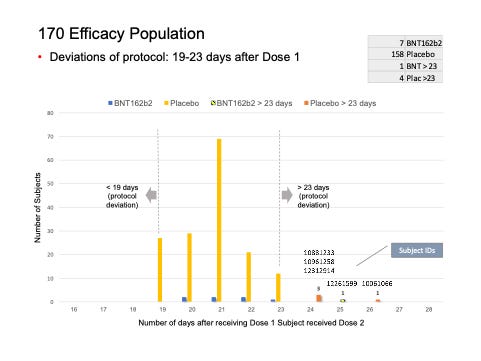

The distribution of subjects’ timing of the second vaccine dose:

What did the analysis of the 170 subjects show?

We found five subjects whose dosing interval between Dose 1 and Dose 2 fell outside the 19- to 23-day window.

C4591001 1006 10061066 (26-day interval), placebo

C4591001 1088 10881233 (24-day interval), placebo

C4591001 1096 10961258 (24-day interval), placebo

C4591001 1226 12261599 (25-day interval), vaccine

C4591001 1231 12312914 (24-day interval), placebo

KEY

C45910011000-44448-digit number 1000 – xPfizer TrialSite IDSubject ID by Site

Whilst we understand the temptation of clinical trial specialists to include these subjects in the Final Analysis of Efficacy, this is not how clinical trials are conducted. An important part of any clinical trial is the removal of subjects who did not follow the trial protocol from analysis. If a deviation in the protocol is to be included, an appropriate amendment must be filed.

Why, then, is the extension of the dosing interval to 42 days so important?

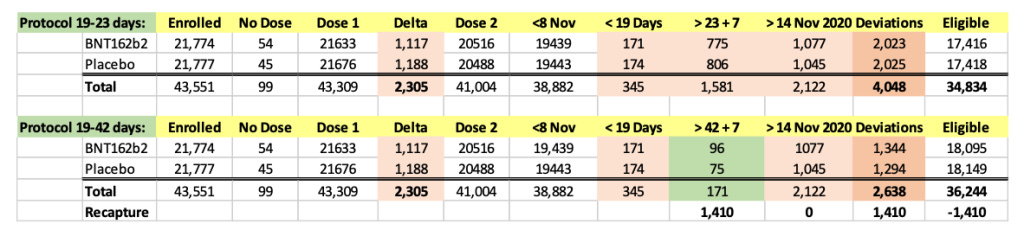

We were intrigued by such a widening of the dosing interval, and further conducted a brief analysis of the all the participants enrolled into the trial. When one looks at the Excel table below, he can see that the trial cutoff date for consideration of the EUA was 14 November 2020. Hence, nobody who received Dose 2 on 8 November 2020 and after could be part of the evaluable population for efficacy, as Dose 2 plus seven days would be after 14 November 2020. From the enrolled population, after elimination of a) those who did not receive their two doses and b) those whose dosing interval fell below 19 days and after 42 days, we can compare how many patients could be recoverable if the “predefined window” was 19-42 days versus 19-23 days. The undocumented change in the protocol (i.e., without an amendment) enabled Pfizer to include an additional 1,410 subjects in the analysis, because – by adding 19 days – Pfizer was able to recover 1,410 patients who were otherwise ineligible for the efficacy analysis. Those 1,410 enabled the inclusion of the four placebo patients and one BNT162b2 patient in the 170 population. (See chart below.)

The 170 patients came only from 66 of the 153 sites, even though all patients enrolled in the trial should have been eligible to be included in the Final Efficacy Analysis. As a team, we intend to audit the sites that enrolled patients in this trial.

Questions continue to arise. After this deep dive, we still have concerns about some of the other subjects that demand answers.

Patients in the 170 who had other major protocol deviations

Subject C4591001 10681082, completed the protocol and received his or her second dose on the 21 September 2020, became symptomatic on 1 November 2020 and tested positive on 2 November 2020. However, this patient is listed as having a protocol deviation of Dosing Administration Error (subject possibly did not receive correct dose of the vaccine). This was already known according to documents dated 30 November 2020 and reinforced again in documents dated 1 April 2021. This subject should not be part of any efficacy analysis. We have cross-checked the errata documentation in case an error of documentation had occurred and could not find it pertaining to this subject.

Subject C4591001 12313895 received his or her second dose of the vaccine on 13 September 2020. The patient developed COVID symptoms on 3 October 2020 and had a positive swab, making him or her one of the patients in the evaluable efficacy population. However, this patient is found on a list dated 30 November 2020, having important protocol deviations, having received blood or plasma products within 60 days of enrollment through conclusion of the study. This subject should not be part of any analysis of efficacy. We also cross-checked this subject with the errata document.

Other issues uncovered in our 170 Final Efficacy Analysis

Subject C4591001 44441224 received his or her second dose on 13 October 2020 and had first symptoms present on 25 October 2020. The subject had a positive swab, which was included in the data analysis. But he or she requested withdrawal from the trial on 12 November 2020. This raises ethical questions about using their data in a study.

Subject C4591001 10161004 received his or her second dose on 19 August 2020, developed fever, new loss of taste or smell, muscle pain and a sore throat on 21 August 2020. A nasal swab, collected on 8 September 2020 for the illness episode of 21 August 2020, was negative. The patient re-presented again on 17 October 2020 with a new loss of taste or smell and sore throat, and this time the COVID swab was positive, and the patient was included in the evaluable population. This highlights the tenuous nature of COVID diagnosis.

Subject C4591001 10921130, received his or her second dose on 22 September 2020, presented with COVID illness on 12 October 2020 and tested positive. Intriguingly, the patient is also found on the list of patients withdrawn from the trial for achieving the endpoint of the trial.

Subject C4591001 11681007 received his or her second dose on 1 September 2020, had one illness visit on 7 October 2020, had a swab dated 6 October 2020 that was negative, and another swab on 8 October 2020 that was positive.

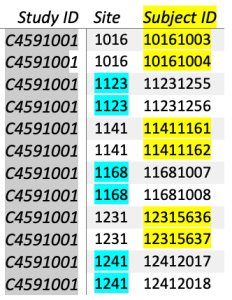

We also noted interesting coincidences of these 170 in a trial of nearly 44,000 enrolled subjects and an evaluable group of around 37,000, where every patient had equal chances of reaching the evaluable analysis. There were six paired instances of sequential numbers.

However, going back to the ‘predefined window’ issue, when did the doubling of a dosing interval of a novel drug seemingly become an acceptable practice?

The Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) for Phase 1 of this study was finalized on 18 November 2020 and approved on 27 November 2020, chronologically after the Phase 1/2/3 SAP of this study, which was finalized on the 2 November 2020, showing that Pfizer disregarded chronological order. [https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-fa-interim-sap.pdf]

This plan, as described before in the Clinical Protocol, described a study design of a two-dose schedule separated by 21 days. (See below.)

[https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-fa-interim-sap.pdf – page 11.]

However, for the first time found in the Analysis sets, the predefined window had a number assigned to it…

[https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/125742_S1_M5_5351_c4591001-fa-interim-sap.pdf, p. 25.]

Conclusions

We are now in an intriguing situation where the endpoint for immunogenicity data for Phase 1, has a visit window of 19 to 23 days; but for Phase 2, for the same immunogenicity data of the same drug, the window was 19 to 42 days. They had not met the threshold for final interim analysis within the 19- to 23-day window but managed to meet it by changing the threshold.

This highlights questions of when the data lock happened, and if the “predefined window” is in fact a post-hoc defined window. Questions arise as to why ambiguity was allowed with regards to the words “predefined window” throughout the trial, in which a number was not defined in all the analysis sets.

We identified that seven patients – five outside of the dosing window and two with major protocol deviations – were part of the final efficacy analysis; therefore, the basis on which the EUA was granted must be revisited, as this brings the evaluable population down to 163, which is below the final threshold for interim analysis. So many norms in society have fallen during the pandemic. If the scientific community is to move forward with integrity, it cannot allow practices like this to stand.

As a team of volunteers, we continue our audit of all the sites with publicly available information.

An extraordinary amount of taxpayer money was used for the Pfizer trial whose Primary Investigators (PIs) may have not followed the trial protocol correctly. In normal circumstances, clinical trials are funded by the company running the trial from their research budget. What we have found in these documents calls into question the validity of the clinical trial results, as well as the potential misuse of billions of United States taxpayer dollars.

This Excel file of the data used to for this report is provided for those who would like to check the authors’ work and/or do their own analysis.

The authors’ have produced two “explainer videos” to put the report in layperson terms. Those videos can be viewed here.

Authors: Jeyanthi Kunadhasan, MD, FANZCA; Ed Clark, MSE; and Chris Flowers, MD - War Room/DailyClout Pfizer Documents Analysis Project Volunteers on Team 3.

This report was originally posted on DailyClout.

From 44,000 to 170? Nothing suspicious there.

A tremendous amount of work. Thank you.